Just Blame Al

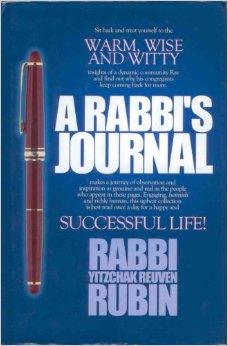

The following is from our first book, A Rabbi’s Journal…..I find the lessons very potent for today as well..enjoy

Just Blame Al

By Harav Y. R. Rubin Shlita

I would like to ask the readers to spare a moment for Al. The past few months have witnessed enormous damage being wrought on much of the state of California. Unprecedented rainstorms have flooded whole tracts of land, thousands of homes have been lost and entire communities now find themselves under water. What has caused such dramatic chaos? A weather system named El Nino.

Now I’m no weather boffin so I can’t explain what this El Nino is or why it has now become such a menace; be that as it may this storm front has a name — El Nino — and that’s where Al comes in. Al lives in California, his family name is Nino, and so his telephone book listing reads Al Nino — get it?

Well, poor innocent Al Nino has come in for all sorts of telephone calls. Folk demanding that he stop mucking about with the weather, irate farmers calling in the middle of the night, asking when he will turn the rains off. The seventy-five-year-old army veteran is at his wits end, but Al is a philosophical sort — “People need someone to blame,” says Mr Nino — and no, he will not change his telephone number, after all “It will all blow over.” Yet people need someone to blame, it seems to make life’s passage a bit easier.

To the Torah Jew blaming others isn’t enough — it doesn’t absolve us from our responsibilities. Learning about ourselves is helpful when we use that knowledge to gain insights on how we can grow and overcome life’s difficulties. There is an expression used of late, “stuff happens”— it points to a simple fact of existence: things happen, not things we would wish for — yet they happen and it’s down to us to see this ‘stuff’ for what it is — an opportunity to expand ourselves spiritually. If not the pain has been wrought with no purpose — and that’s sad indeed. Society today tells us that nothing is our own fault — everything we do is because somewhere in our past someone did us some injustice. This may perhaps be a way of understanding why we react in certain ways — but it is not an excuse to do wrong. The Yidden in the Midbar were guilty of this when they fashioned the Golden Calf. There is a river in Egypt called the Nile — that’s what they were in — “Denial.” When faced with the realization that from that point on they would have to build a relationship with Hashem through a service of mitzvos, they went into denial — everything they had experienced was set into a different light, one that would suit them. They sought a man-made Moshe that they would somehow control, one they could blame if things went wrong.

Chazal tell us that honoring one’s parents is one of the most difficult of the Aseres Hadibros. It seems strange; one could think that paying back one’s parents with some degree of gratitude would be quite understandable. After all they have done so much for us, playing a pivotal role in our very creation. However, people go into denial all to often. Any student of human behavior will know how much hostility and anger many harbour against their parents. They feel that their parents made tremendous mistakes in bringing them up — and because of these misdemeanors they are now themselves flawed and wounded. Well, parents are human — and are who they are, given their own experiences. It is an arrogance for anyone to judge them and then expect that when found guilty; our own psychological quirks will somehow become more acceptable. Life is about seeking out one’s inner faults and trying to overcome them. It is right to try to understand what makes us who we are — but then we are meant to overcome any emotional baggage that hinders us — not by blaming others, which only enslaves in hate — but by using past experiences to gain positive insights. Many are the times when young students who are becoming more involved with a Torah lifestyle will tell me how they are angry at their parents. “Why couldn’t they have sent me to a proper school? Why did they not keep Shabbos and instill in me a feeling for true Yiddishkeit” “Stuff happens!” I’ll answer. “You don’t know what their life was all about, rather be glad of what you have found and don’t waste your efforts on blaming them.”

I once went to visit a Chassidishe Yid who was sitting Shiva for his late father. I knew that the niftar was not frum and that he had made his son’s life quite difficult when, as a boy, he became frum. Despite, or perhaps because of, his background, the fellow had work hard and acquired a respectable position as a mechanech and communal leader. After Maariv my friend’s son got up to speak of his late grandfather. The young Chassidishe kollel yungerman stood there about to eulogise someone who was “a finer” but definitely not the Zaidy such a varmer Chosid would have felt close to. And yet, he spoke movingly of his “Grandpa’s” midah of Simcha — how he always laughed, and brought that laughter to everyone he met. As the young Talmid Chochom spoke I gazed at his father — and watched as tears rolled into his greying beard.

Some months later I had occasion to learn together with that oveil — it was Parshas Ki Sisa and we were learning of how Moshe Rabbeinu asked to see Hashem’s Glory. Some explain that Moshe was asking to be enabled to comprehend Hashem’s unique nature. Others explain that in fact Moshe was asking to see the future so as to better understand the reasons for present realities. Hashem’s reply was “You cannot have a vision of Me and still exist.” Instead Hashem tells Moshe to stand on the rocky mountainside — then, according to the Chasam Sofer, the Posuk indicates that by looking after events have happened (achorai) one will be able to begin to understand why things happen as they do. Before time has passed “ufonai” you fail to comprehend such matters.

My friend turned to me and said, “You know, all through my children’s youth I was frightened – because of no fault of theirs they were lumbered with grandparents who must have seemed — as aliens to them, they didn’t know of Shabbos, Yomtov — or in fact anything that was central to our lives. Everyone else had Zaidys and Bubbies, my kids had Grandma and Grandpa. There were no shared seders, no special Yomim Tovim — and to make matters worse they spoke of things we didn’t want our children to encounter. I felt guilty because I was the reason for all this difficulty, I tried my best to get through it all, sensitizing my young to the “quirks” of their grandparents. I just hoped that somehow my children would gain through their uninvited experiences. Then I heard my son speak at the Shiva — and I realized, after the fact, that in some way good had come out of it all.”

Perhaps the aforementioned posukim we were learning touched on my friend’s success. The Torah speaks of Moshe standing on a rock — and then being placed by Hashem into a protective crevice. By having a home that was built on the rock of Torah that strived to aspire to ever-greater heights, the children in the family were gently protected by the special care that only Siyata Dishmaya can afford. Instead of blame there was always understanding. Yes, stuff happens but it can be the stuff of light.

לעילוי נשמת

הר”ר יוסף חיים זוננפלד זצולה”ה

נפטר י”ט אדר א’ תרצ”ב